The Slow Death of Wonder

SANDHEEP RAJKUMAR | July 25, 2025

I’ve heard people say smartphones, the internet, social media and everything else have made us less curious. And I couldn’t help but be curious about this assumption itself. And the fact that I think most people are idiots doesn’t help. I call it an assumption because the argument is always innocent until proven guilty.

A good thought experiment here would be to go back to a time that smartphones didn’t exist and take up one of the most curious men who ever lived. Leonardo da Vinci. Our assumption should be able to prove that Da Vinci was Da Vinci because he didn’t have a phone. I understand that this is a little reductionist of me, but it still proves our point. Da Vinci didn’t have a smartphone but neither did anyone else back then. So why was he the only one building flying machines and dissecting corpses?

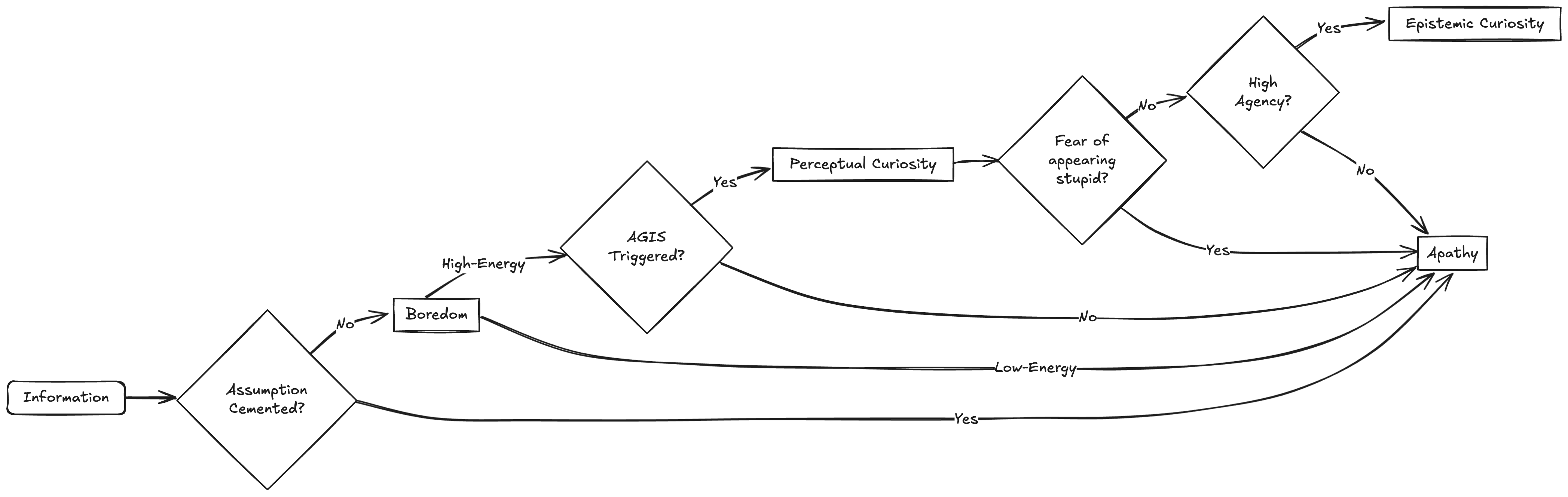

Smartphones don’t kill curiosity but they do kill boredom. Boredom is like the soil that curiosity grows in. And throughout my life, I’ve come to realise that there’s actually a good kind of boredom and a bad kind. Actually, if you wanna get all nerdy and scientific, there’s supposed to be five different kinds of boredom but for the sake of the reader, I’m not going to get into that. And good and bad is a poor choice of words because they’re neither very descriptive nor quantitative. You could look at them in terms of energy though. High-energy boredom and low-energy boredom. Only high-energy boredom can spark curiosity. Low-energy boredom will just sink you into apathy. But again, most of us already know this, or at least a version of it. Although it is quite interesting to think about what leads a person to either be high-energy bored or low-energy bored.

Another question I had was if you require a baseline set of knowledge in order to be curious about something in the first place. I thought about some of those videos of Neil deGrasse Tyson or Brian Greene explaining the actual shape of the universe. I’ve noticed this to be a very good example because some people are left with about a thousand questions while some say “Oh cool” and move on. And I could tell you exactly what kind of people each of them are as well, which leads me to the following question.

Does curiosity only emerge when you’re close enough to grasp the next layer of understanding?

I started calling this little window as the “Almost Get It State” (through lack of a better name). Or AGIS. Basically a zone of tension between ‘what you know’ and ‘what you feel you could know’. But what about kids? Kids are some of the most curious little beings you’ll ever come across. And we’ve got a lot more baseline knowledge than they do.

So, does our AGIS have an age-relative maxima and minima?

Because as we grow older, our capacity for abstraction actually increases. So why aren’t we more curious than kids are? Pride, ego and shame are definitely part of the answer. When you grow up being told you’re smart, you often avoid the possibility of failure just to protect that identity. So maybe our AGIS does widen as we get older but we just tend to access less of it? Which says a lot about the importance of psychological safety in order to get curious in the first place. There’s also some factors other than shame I can think of,

Assumption Cementing: To think you already know what you’re supposed to know. Agency Loss: A belief that your exploration will have no value. Fear of Exclusion: Almost a very primal survival mechanism.

Another factor I noticed was actually about the stimuli that triggers your curiosity in the first place. Curiosity that is triggered by external stimuli is very different from the curiosity triggered by internal stimuli. And they’ve got cool-sounding names as well. Perceptual Curiosity (i.e external) and Epistemic Curiosity (i.e internal).

Perceptual Curiosity: Triggered by novel stimuli. Epistemic Curiosity: Triggered by a desire for knowledge.

And you don’t have to be Einstein to figure out which one lasts and which doesn’t. But again, they serve different purposes. All curiosity starts off as perceptual but if it does not convert to an epistemic curiosity in time, it WILL die out. Which is why we start off learning things with so much energy and then just get bored (there’s other factors at play here too but this is a big one).

So, how does all of this actually work in practice?

Think of it this way, every piece of information that hits you is pretty much asking the same question. Are you going to let it bounce off your existing assumptions, or are you going to let it create some productive tension? Curiosity isn’t random. It follows predictable pathways, and most of those pathways have failure points where we bail out and choose comfort instead. I also made a diagram that maps out what I think is happening in those moments leading to genuine curiosity.

Your phone can be a curiosity-killer if you use it to doomscroll away every moment of high-energy boredom. But it can also be the thing that drops you into a YouTube rabbit hole at 2 AM because you suddenly need to understand how quantum tunneling works, or why the Roman Empire really fell. At this point it’s safe to say that smartphones definitely aren’t killing your curiosity. But you know what is?

You.

There’s almost zero reason (other than evolution) for your assumptions to be set in stone. Because the thing is, wonder doesn’t die. It just gets buried under assumptions that we think are too heavy to lift, unless we still believe it's worth digging.

And the moment we stop being curious about what lies beyond our assumptions, we stop growing.